Content archived on 19 April 2025

These days, many of us take the good health and safety record on our railways for granted, but it has mostly come about through the work of the Railway Inspectorate (RI) – celebrating 175 years of service this year – and is now part of the Office of Rail and Road (ORR).

Railway companies sprang up somewhat haphazardly across Britain in the early 1800s, with the first passenger carrying line in 1807 – it was horse drawn. 1825 saw the first locomotive-pulled passenger railway in the world.

In 1840, through the Railway Regulation Act, the Board of Trade appointed the first Railway Inspector to inspect construction and equipment of new railways. The Regulation of Railways Act 1871 is generally regarded as the founding legislation of the modern inspectorate. This Act consolidated previous provisions regarding the appointment of inspectors and the inspection of works. It also provided formal powers for the investigation of accidents and recommend ways of avoiding them.

Other legislated powers to enable inspectors to have an impact on a growing industry:

- 1840 companies are required to give one month's notice of intention to open new railways

- 1842 powers to postpone opening of new railways on safety grounds

- 1871 powers to investigate train accidents

- 1900 powers to investigate accidents to railway staff

Since then, by investigating, highlighting and reporting on health and safety issues, railway inspectors in their various incarnations has helped bring about huge changes and saved countless lives.

Exploding engines, broken rails, lack of signals, gas-lighting fires, inadequate brakes, cows on the line – these were some of the dangers on the fledgling railways.

1872 - bridge of Dun boiler explosion

Every year, railway inspectors looked at accidents and suggested improvements such as continuous brakes, guidance on boilers to avoid explosions, block signalling, rules for lookout men, designing cabs for driver protection in collisions, setting noise level maximums in driver cabs, and rules for emergency evacuation from trains.

Great changes were made, but other issues arose. Even well into the mid twentieth century inspectors reported on numerous fires in diesel engines, accidents due to staff error and 'malicious' actions by the public such as stone throwing or attempts to derail by putting objects on the line. Some of these, including dealing with cows on the line and preparing for weather conditions, still feature in our safety inspections today.

Safety by design has been a feature in much of the work. The incidences of people being struck by trains while leaning out of windows and people falling out of trains eventually led to automatic locking doors and sealed windows in new stock. Welded rails meant fewer derailments due to track problems and level crossings developments meant safer ways to cross the line.

One seemingly simple improvement for London Underground in the 1980s – toilets for staff at platform level - surely made work more comfortable for staff and therefore safer for passengers.

1994 saw the introduction of the Safety Case Regulations where every railway operator (trains, stations and infrastructure controller) had to prepare and have accepted a 'safety case'. This is a document in which operators demonstrate that they have the resources, capability and commitment to ensure that safety practices are followed at all times and the safety of passengers and railway staff are not placed at risk. This regulation has since been updated.

Adrian Ling is ORR's longest serving inspector, with 44 years' service, starting with the Health and Safety Executive (HSE). Looking back over the 175 year history of RI, Adrian believes there have been some significant improvements in passenger safety brought about by changes in legislation as a result of disasters, but the improvement in staff safety has been mainly brought about by a change in culture.

HSE must take a lot of the credit for raising the profile of health and safety generally (and it's disappointing that health and safety has got a bad name because of risk aversion and misrepresentation) but I think that a lot of the improvement has been brought about by the activities of HMRI by nagging the industry to keep health and safety at the top of the agenda.

ORR continues this focus on worker health and recently published a report on four years of work in this important area.

Safety never stops. It's an ongoing story. We have a long, proud history of making railways safer. We continue to work with the industry and other partners to design out health and safety issues as much as possible and be vigilant in predicting and preventing issues before they happen.

Safety improvements by numbers

| 1874 | 1983 | 1992-93 | 2014-15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 788 workers killed on railways | 28 railwaymen killed at work | 11 railway workers killed at work | 4 railways workers lost their lives at work |

| 69 people killed on the railway (excluding trespassers 146 and suicide 212) | 39 people killed on the railway (excluding trespassers 136 and suicide 108) | 14 people killed on the railway (excluding trespassers 22 and suicide 293) | |

| 695 million passenger journeys on British Railway | 769 million passenger journeys on British Railway | 1.66 billion passenger journeys on main line railway | |

| 565 million passenger journeys on metro railways* | 787 million passenger journeys on metro railways** | 1.3 billion passenger journeys on London Underground |

*Metropolitan railways include Tyne & Wear Metro, London Transport Railways and Strathclyde Glasgow Underground Railway

**Metropolitan railways include Tyne & Wear Metro, London Transport Railways, Strathclyde Glasgow Underground Railway and Docklands Light Railway

Safety case studies

The 1950s saw two terrible accidents; on 8 October 1952, at Harrow and Wealdstone Station, the Up Perth sleeper train failed to observe stop signals in patchy fog, and collided at 60mph with a local train standing in the station. Before the signalman could act, an express bound for Liverpool & Manchester collided with the wreckage. A total of 112 people died.

The subsequent RI report together with the further collision at Lewisham which killed 90 people five years later, accelerated the introduction of the Advanced Warning System (AWS), which gave the driver an in-cab indication of signal aspect, and applied the brakes automatically in the event of a signal overrun.

A serious derailment occurred at Hither Green on 5 November 1967; 49 people died when a busy 12 car train derailed at 70mph due to a piece of rail-head having broken off at a rail joint. The report into the accident highlighted the effects of newer small-wheeled trains with unsprung motors on older track designs, and recommended that the laying of Continuous Welded Rail (CWR) be accelerated to eliminate rail joint defects of this type.

In the 1980s, fatalities due to falls from moving trains were on average 20 per year and were a growing public concern. In 1991/92 HMRI were part of an HSE investigation which looked into the cause of these incidents including examinations of the design, operation and use of train doors and locks and the associated installation and maintenance procedures used by British Rail.

The subsequent published report (passenger falls from train doors, report of an HSE investigation) found that there was evidence of poor maintenance procedures, doors and locks poorly fitted and a design failure. The report, published in 1993 and its recommendations implemented by the industry, resulted in a significant decrease in fatalities and serious injuries.

David Keay, our deputy chief inspector, shares his top five safety improvements brought about by RI:

- The drive for worker safety: there were 734 workers killed in 1887 amid an acceptance that this was an inevitable consequence of operating and maintaining a railway. Today we do not accept any work related fatalities

- The drive to prevent derailments: by locking points (1889), prevention of overspeed (train protection warning system 1999), the integrity of stretcher bars between point blades (1850s then after Potters Bar and Greyrigg)

- The drive to prevent conflicts between the public and the railway: by closure of level crossings including 100s of footpath crossings (driven onwards by the two tragic deaths at Elsenham)

- The drive for the protection of the travelling public: crash protection in carriages, safety glass, removal of gas lighting

- The drive to prevent train collisions: by introducing signalled blocks that only permit one train at a time into a section (1889), the requirement for advanced warning system (AWS) and in 1999, train protection warning system (TPWS) on all junction signals.

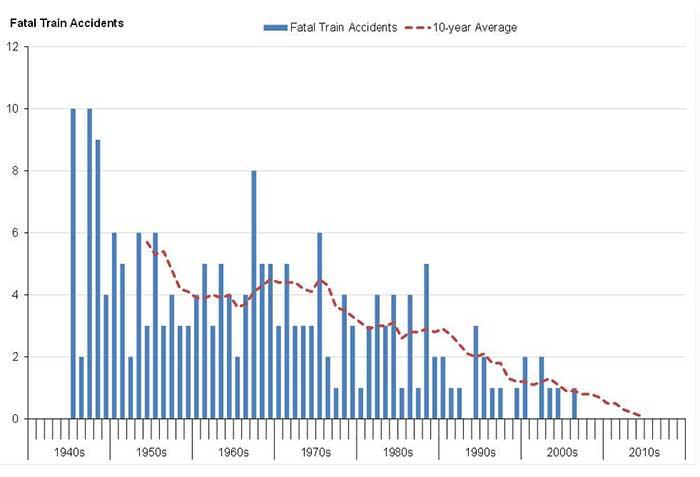

Fatal train accidents - 10 year average